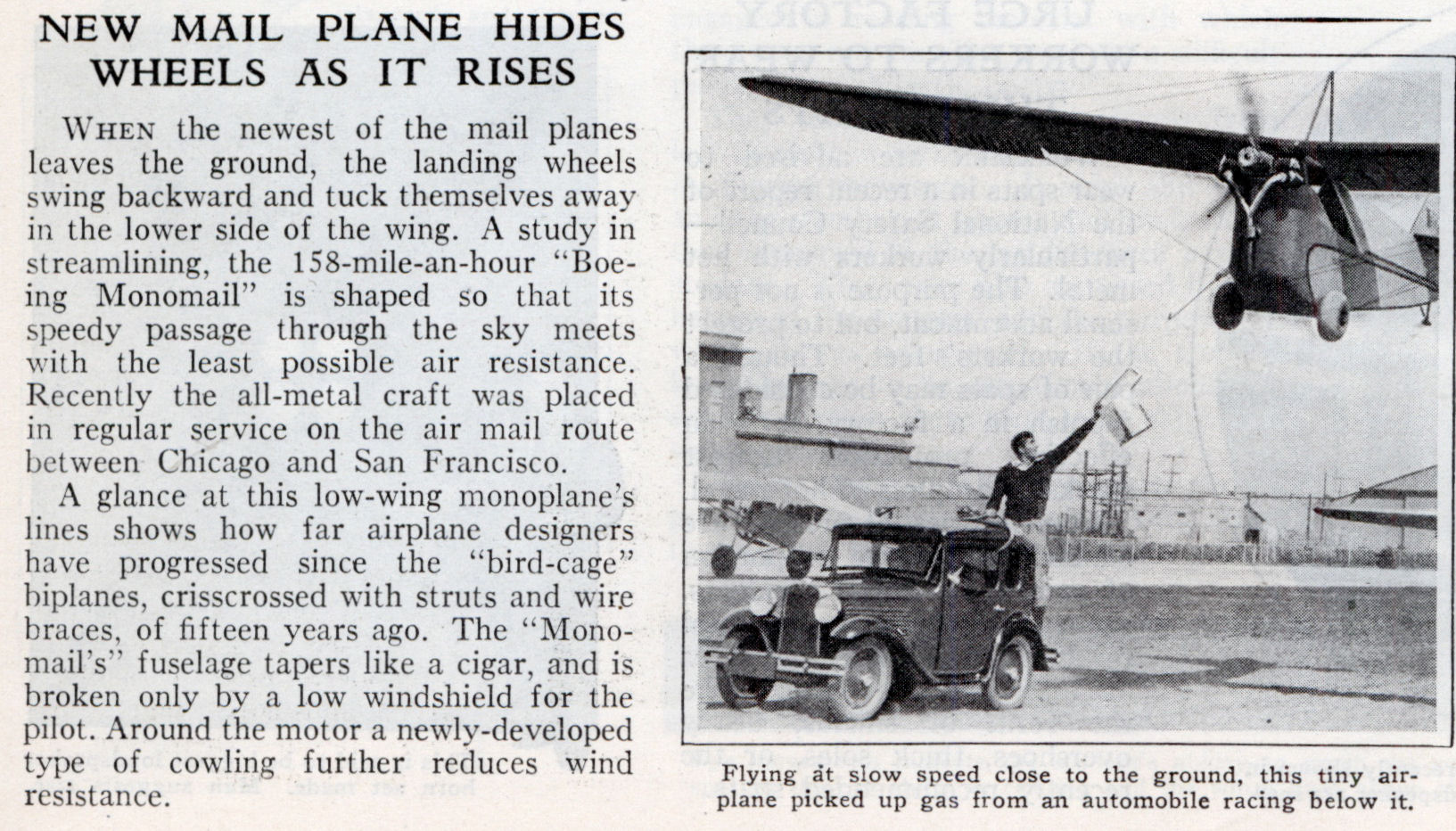

Refueling aircraft in-flight got it's beginning when men standing on fast driving cars would hand cans of gas to aviators as their slow flying aircraft passed overhead. As aviation evolved from cloth covered biplanes hauling mail across the continent to metal mono-winged streamlined aircraft being used as war fighting machines, so did the method for keeping them aloft longer need to evolve.

Refueling aircraft in-flight got it's beginning when men standing on fast driving cars would hand cans of gas to aviators as their slow flying aircraft passed overhead. As aviation evolved from cloth covered biplanes hauling mail across the continent to metal mono-winged streamlined aircraft being used as war fighting machines, so did the method for keeping them aloft longer need to evolve.

Aircraft-to-Aircraft In-flight Aerial Refueling can be traced back to November 1921 when a wing walker took a gas can and walked across the wing of a Lincoln Standard; stepped over to Curtiss JN-4; and poured the gas into the "Jenny's" tank.

Aircraft-to-Aircraft In-flight Aerial Refueling can be traced back to November 1921 when a wing walker took a gas can and walked across the wing of a Lincoln Standard; stepped over to Curtiss JN-4; and poured the gas into the "Jenny's" tank.

On Oct. 5, 1922, Lts. John Macready and Oakley Kelly set a world endurance record of 35 hours, 18 minutes, 30 seconds in their Fokker T-2 airplane over San Diego, Calif. If they had not run low on fuel, they could have remained in the air until personal fatigue or mechanical difficulty forced them to land.

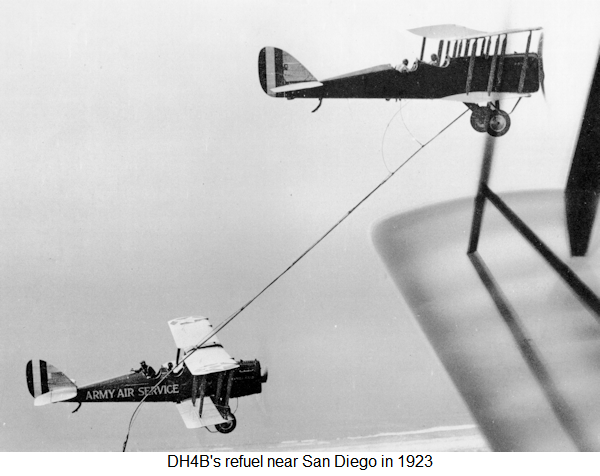

To eliminate the fuel limitation problem, the fliers at Rockwell Field, San Diego, developed a system for mid-air refueling between DH-4B airplanes. The first successful aerial refueling took place on June 27, 1923, when a DH-4B carrying Lts. Virgil Hine and Frank Seifert passed gasoline through a hose to another DH-4B flying beneath it carrying Lts. Lowell Smith and John Richter.

On June 28, 1923 another refueling flight was made in an attempt to break the world record set by Macready and Kelly in the T-2 in 1922. Unfortunately, a gasoline valve in the receiver airplane became plugged, and Smith had to make a forced landing in some mud flats near North Island after almost a full day in the air.

Two months later on Aug. 27-28, Smith and Richter made an endurance flight which lasted 37 hours, 15 minutes, with 16 refueling contacts. During this flight, they set 16 new world records for distance, speed and duration. On Oct. 25, 1923, Smith and Richter flew nonstop from the Canadian to the Mexican border, a distance of 1,250 miles, by being refueled three times while in the air. The theory of extending the range of an airplane by mid-air refueling had became a demonstrated fact.

Then between the 1st and 7th of January 1929, the 'Question Mark'; a Fokker C-2A trimotor and it's five man crew would establish a new world record for an endurance flight. Their Fokker C-2 transport stayed aloft for 150 hours and 40 minutes. Two Douglas C-1s took turns refueling them with a hose lowered from the tankers through a trapdoor in the top of the 'Question Mark'.

Then between the 1st and 7th of January 1929, the 'Question Mark'; a Fokker C-2A trimotor and it's five man crew would establish a new world record for an endurance flight. Their Fokker C-2 transport stayed aloft for 150 hours and 40 minutes. Two Douglas C-1s took turns refueling them with a hose lowered from the tankers through a trapdoor in the top of the 'Question Mark'.

During the flight, the 10,000-pound C-2A was refueled in flight by two modified Douglas C-1 transport aircraft. A large question mark was painted on each side of the receiver aircraft's fuselage, intended to "provoke wonder at how long the aircraft could remain airborne," according to Air Force history experts. One fuel transfer actually took place over the Rose Bowl in Pasadena while Georgia Tech and California were playing on the field below. The flight ended after the Fokker developed engine trouble. During the flight, the two Douglas refueling aircraft passed 5,660 gallons of fuel in 43 sorties; 12 of which happened at night.

After the success of the Question Mark's Jan. 1929 aerial refueling flight the U.S. Army Air Corps spent little time thinking about aerial refueling. This was not to say that nothing was done with the air refueling concept through the 1930s, but most was accomplished thanks to civilian aviators.

From 1930 until 1937, the Royal Air Establishment conducted a series of air refueling experiments. The RAF looked at air refueling not so much as a way to extend an aircraft's reach, but more to help lighten take-off weights. Especially since the League of Nations was considering bomber size restrictions - less fuel on take-off, meant more bombs could be carried by the aircraft.

The experiments that began with the Question Mark's techniques were improved upon by barnstorming efforts of the dangle and grab method of in-flight refueling. To accomplish this, the tanker aircraft would feed out a hose that someone in the receiving aircraft reached out and grabbed.

In September 1934 the newly patented looped-hose aerial refueling system was introduced. This new technique put most of the operational effort on the tanker crew. Both the tanker and receiver trailed cables with grapnels on the ends. The receiver flew a straight line, while the tanker crossed its path from behind allowing the grapnels to catch. The receiver then reeled in the cables, along with a hose from the tanker. Once the two aircraft were connected with about 300 feet of hose, the tanker pilot would then maneuver to a higher position and let gravity take care of rest.

These experiments continued until 1937, but by then most people had decided that air refueling offered a limited application at best. Aircraft technology had surpassed any perceived need for air refueling.

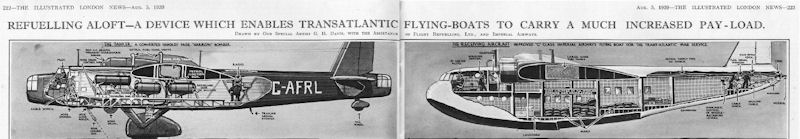

Commercial interests soon returned to the idea of air refueling. Companies began looking at "flying boats" to connect the widespread British Empire, and they hoped air refueling would improve their operation. The looped-hose system was refined in 1939, when Imperial Airways began the first commercial air refueling operations. The company flew Short S.30 flying boats for weekly mail service flights between Southampton, England, and New York City. FRL used two obsolete Handley Page HP.54 Harrow bombers as tankers -- one at Gander, Newfoundland, and the other at Rineana, Ireland. These air refueling operations were not intended to extend the flight times, but to allow the flying boats to take off with minimal fuel and more mail.

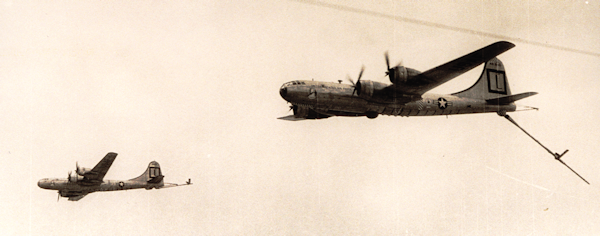

These KB-29Ps prepare for in-flight refueling as part of an operation.

(U.S. Air Force historical photo)

On July 19, 1948 the 43rd & 509th Air Refueling Squadrons were activated at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base, AZ and Roswell Air Force Base, NM, in preparation for the assignment of tanker aircraft. These two squadrons were the first air refueling units in the U.S. Air Force. They began receiving tanker aircraft in late 1948 when some B-29s were modified to carry and dispense fuel.

The introduction of dedicated tanker aircraft and crews allowed SAC to extend the range of its B-29 and B-50A bombers. Concurrently, SAC and the Air Force made the decision to equip all future bombers with an in-flight refueling capability. However, the loop-hose system proved unwieldy and difficult, particularly in bad weather. With a two-and-a-half-inch diameter refueling hose, the FRL-developed system transferred fuel at a rate of only 110 gallons per minute. With new high-speed, high-altitude jet bombers coming on line, capable of operating at night and in bad weather, it quickly became apparent something better was needed.

The introduction of dedicated tanker aircraft and crews allowed SAC to extend the range of its B-29 and B-50A bombers. Concurrently, SAC and the Air Force made the decision to equip all future bombers with an in-flight refueling capability. However, the loop-hose system proved unwieldy and difficult, particularly in bad weather. With a two-and-a-half-inch diameter refueling hose, the FRL-developed system transferred fuel at a rate of only 110 gallons per minute. With new high-speed, high-altitude jet bombers coming on line, capable of operating at night and in bad weather, it quickly became apparent something better was needed.

Interestingly enough, Boeing already had a better system in mind. The company developed a "flying boom," which featured a telescoping pipe with fins at the nozzle end. The fins were termed "ruddervators" because they functioned as both rudders and elevators. The boom operator, sitting in the B-29's converted tail turret, literally flew the boom into a receptacle on the upper fuselage of the receiver aircraft. This design allowed more positive control of the air-to-air refueling operation and, with the boom's four-inch diameter, it offered much faster fuel transfer.

Subsequently, SAC converted some aircraft to a probe and drogue system, using another design pioneered by Flight Refueling International. It featured a refueling hose mounted on an electrically-driven reel inside the tanker, with the receiver aircraft taking on fuel through a fixed refueling probe. While initially tested with bombers, the design later proved particularly useful with fighter aircraft.

However, the B-29's aging airframe and limited fuel offload capability definitely made it an interim tanker (although the last B-29s didn't retire from SAC until November 1957). In the meantime, Boeing came up with an improved tanker aircraft, the KC-97.

Based on the Model 377 "Stratocruiser" trans-oceanic airliner, the KC-97 featured a unique double-bubble fuselage with plenty of space available inside for fuel, cargo and passengers, combined with the wings and engines of the Boeing B-50.

The C-97 was the cargo/transport version of the B-29. If you fatten the B-29's fuselage, use the same wings, tail and engines you have a cargo plane. The prototype first flew in 1944 with the first production C-97A in 1949. Boeing also developed a practical in-flight refueling boom about the same time. Previously, the Air Force had experimented with a trailing hose technique with some success, but Boeing's boom changed the state of the art overnight.

The first prototype YC-97A transport served with the Military Air Transport Service during the Berlin Airlift in 1949 and went into full production that same year. In 1950, Boeing introduced the KC-97 variant, equipped with the flying boom system.

Dubbed the "Stratotanker," the KC-97 quickly became the most numerous SAC tanker, with more than 800 built. The first aircraft went into service with the 306th Air Refueling Squadron at MacDill AFB, Fla., in 1951. By 1953, SAC operated almost 30 air refueling squadrons with 502 tankers, with the majority of the squadrons flying KC-97s. Nearly every B-47 wing had a KC-97 air refueling squadron assigned to it. When B-47s deployed overseas, their tankers went with them, enabling the mass deployment of entire wings of bombers to bases in Europe and the Far East under Operation Reflex.

However, even the new KC-97 operated with several limitations. While a single KC-97 could adequately refuel a B-47, it took two or more to refuel a B-52. Additionally, it took a long time for a fully laden KC-97 to get to its cruising altitude. This forced SAC to deploy its tankers for extended periods to locations in Alaska and Canada, strategically located along the routes the bombers would use to get to their targets. With adequate warning, the KC-97s would get to altitude in time to service the bombers coming from the United States.

However, the speed disparity between the KC-97 and its receivers provided the biggest problem. During aerial refueling, the bomber had to slow down and drop to the KC-97's altitude. Once the aircraft connected, the tanker went into a dive, allowing the bomber to maintain enough speed to stay in the air. As the receiver took on more fuel, it grew heavier, which made the maneuver -- known as "tobogganing" -- even more difficult. When done in poor or marginal weather, the experience proved even less enjoyable for the aircrews. Once the two aircraft completed the refueling, the jet bomber had to climb back up to its cruise altitude, which burned a lot of the fuel it had just taken on.

As an example, Strategic Air Command conducted Operation Power Flite in 1957. Designed to test and display the intercontinental capability of the B-52, the mission consisted of three B-52Bs from Castle Air Force Base, Calif. These three aircraft flew around the world, a distance of 21,135 nautical miles, and successfully completed the route in 45 hours and 19 minutes.

The three B-52s of Operation Power Flite required the support of 78 KC-97s, plus several more standing alert at bases along the route in case of adverse winds. The operation showed it took two KC-97s to provide 26 percent of one B-52B's refueling requirements.

☛ Goleta Air Museum Boeing C-97 Stratofreighter - Stratotanker Page ☚

By this point, though, the Boeing Corporation had already initiated developing, with its own funds, a new turbojet aircraft. Boeing officials invested in such an aircraft because it would be able to serve as a tanker, a military cargo aircraft, and even a commercial airliner. In November 1953, SAC issued its requirement for 200 jet tankers. The Air Force received three proposals in response -- paper-only designs from the Douglas and Lockheed Corporations. But while the other companies talked about possible designs, only Boeing had an operating model. Because of the urgency of SAC's need, the Air Force procured 29 KC-135 Stratotankers as an interim measure in 1957. The Air Force ended up procuring 830 KC-135 "StratoTankers".

By this point, though, the Boeing Corporation had already initiated developing, with its own funds, a new turbojet aircraft. Boeing officials invested in such an aircraft because it would be able to serve as a tanker, a military cargo aircraft, and even a commercial airliner. In November 1953, SAC issued its requirement for 200 jet tankers. The Air Force received three proposals in response -- paper-only designs from the Douglas and Lockheed Corporations. But while the other companies talked about possible designs, only Boeing had an operating model. Because of the urgency of SAC's need, the Air Force procured 29 KC-135 Stratotankers as an interim measure in 1957. The Air Force ended up procuring 830 KC-135 "StratoTankers".

For the next 20 years, SAC maintained nearly a one-to-one ratio of KC-135s to B-52s. Often, they set on alert status together, with the tanker providing fuel in a "buddy" fashion. On the other hand, forward basing the tankers to rendezvous with the bombers offered a significant advantage: forward-based tankers had more fuel to give the bombers since they did not have to travel such a great distance. With this in mind, SAC based KC-135s at places like Westover AFB, Mass., and Dow AFB, Maine. Secret agreements with Canada also allowed SAC to base KC-97s at Cold Lake and Namao in Alberta.

Through the years, the Air Force modified the KC-135s. The first modifications began in July 1962 when SAC developed the Q-model. A total of 56 KC-135As received fuel tanks to hold special fuel for the SR-71 and additional communication equipment used during fuel transfer operations. In later years, when the KC-135Qs were refitted with CFM-56 engines, the aircraft were re-designated as KC-135Ts.

Another model (-B) began in July 1964 as Boeing added specialized communications equipment and an air refueling receptacle in 17 KC-135As. Essentially an airborne command post, the KC-135B was re-designated the EC-135C on Jan. 1, 1965.

The two major KC-135 modernization programs began in the 1980s. The KC-135E was refitted with JT-3d engines. By the end of the program, 157 Air Force Reserve and Air National Guard KC-135s were updated. And in July 1984, SAC formally accepted the first KC-135R, equipped with new fuel-efficient CFM-56 engines and more than 25 other updates, such as generators and main landing gear. The KC-135R had 1.5 times the fuel offload capacity of the KC-135A. More than 410 KC-135s were re-engined by June 9, 2005.

In June 1967, SAC published a requirement for an advanced capability tanker to supplement the KC-135 force. While ideal for supporting the bomber mission, planners judged the KC-135 force as inadequate to support a general force deployment of attack, rescue, air defense, and airlift aircraft. Although Headquarters Air Force endorsed the concept, little was done while the Vietnam War continued.

In June 1967, SAC published a requirement for an advanced capability tanker to supplement the KC-135 force. While ideal for supporting the bomber mission, planners judged the KC-135 force as inadequate to support a general force deployment of attack, rescue, air defense, and airlift aircraft. Although Headquarters Air Force endorsed the concept, little was done while the Vietnam War continued.

A tanker support study in 1970 called for adapting a current wide-body transport aircraft as the most cost-effective solution. In December 1973, SAC reissued its tanker requirement, now entitled the Advanced Tanker Cargo Aircraft. Both Military Airlift Command and Tactical Air Command agreed that the new aircraft should be primarily a tanker with an airlift augmentation capability.

Two companies submitted proposals. Boeing based its proposal on its 747, while McDonnell Douglas based its proposal on the KC-10. On Dec. 19, 1977, the Air Force selected the KC-10A as the more advantageous aircraft. While the 747 version offered a larger capacity, the KC-10 was cheaper and offered the ability to take off with a maximum load from a shorter runway. From 1981 to 1990, the Air Force received 60 KC-10s.

SAC originally assigned the 60 KC-10 aircraft to three bases: Barksdale AFB, La.; March AFB, Calif.; and Seymour Johnson AFB, N.C. Following the Air Force's reorganization and the creation of Air Mobility Command in 1992, leaders consolidated the KC-10s at McGuire AFB, N.J. (now called Joint Base McGuire-Dix-Lakehurst), and Travis Air Force Base, Calif.

Both the KC-10 and KC-135, despite their age and heavy use, continue to ensure AMC accomplishes its rapid global mobility mission, as well as sustaining America's deployed forces. In 2009, the last KC-135E model Stratotanker was retired leaving the Air Force's In-Flight Refueling requirements to be handled by the remaining 400 KC-135R (approx) models and the 60 (approx) KC-10 refuelers.

Both the KC-10 and KC-135, despite their age and heavy use, continue to ensure AMC accomplishes its rapid global mobility mission, as well as sustaining America's deployed forces. In 2009, the last KC-135E model Stratotanker was retired leaving the Air Force's In-Flight Refueling requirements to be handled by the remaining 400 KC-135R (approx) models and the 60 (approx) KC-10 refuelers.

In 2011, 179 Boeing KC-46A aerial refuelers were ordered to replace the U.S. Air Force's aging fleet of KC-135 Stratotankers which has been the primary refueling aircraft for more than 50 years. With more refueling capacity and enhanced capabilities, improved efficiency and increased capabilities for cargo and aeromedical evacuation, the KC-46A will provide aerial refueling support to U.S. and allied nation coalition force aircraft.

In 2011, 179 Boeing KC-46A aerial refuelers were ordered to replace the U.S. Air Force's aging fleet of KC-135 Stratotankers which has been the primary refueling aircraft for more than 50 years. With more refueling capacity and enhanced capabilities, improved efficiency and increased capabilities for cargo and aeromedical evacuation, the KC-46A will provide aerial refueling support to U.S. and allied nation coalition force aircraft.

The KC-46A will be able to refuel any fixed-wing receiver capable aircraft on any mission. This Boeing 767 based aircraft is equipped with a modernized KC-10 refueling boom integrated with proven fly-by-wire control system and delivering a fuel offload rate required for large aircraft. In addition, the hose and drogue system adds additional mission capability that is independently operable from the refueling boom system.

Two high-bypass turbofans, mounted under 34-degree swept wings, power the KC-46A to takeoff at gross weights up to 415,000 pounds. Nearly all internal fuel can be pumped through the boom, drogue and wing aerial refueling pods. The centerline drogue and wing aerial refueling pods are used to refuel aircraft fitted with probes. All aircraft will be configured for the installation of a multipoint refueling system.

MPRS configured aircraft will be capable of refueling two receiver aircraft simultaneously from special "pods" mounted under the wing. One crewmember known as the boom operator controls the boom, centerline drogue, and wing refueling pods during refueling operations.

A cargo deck above the refueling system can accommodate a mix load of passengers, patients and cargo. The KC-46A can carry up to 18 463L cargo pallets. Seat tracks and the onboard cargo handling system make it possible to simultaneously carry palletized cargo, seats, and patient support pallets in a variety of combinations.

The aircrew compartment includes 15 permanent seats for aircrew which includes permanent seating for the aerial refueling operator and an aerial refueling instructor.

General Characteristics

Power Plant: 2 Pratt & Whitney 4062

Thrust: 62,000 lbs - Thrust per High-Bypass engine

Wingspan: 157 feet, 8 inches

Length: 165 feet, 6 inches

Height: 52 feet, 10 inches

Maximum Takeoff Weight: 415,000 pounds

Fuel Capacity: 212,299 pounds

Maximum Transfer Fuel Load: 207,672 pounds

Maximum Cargo Capacity: 65,000 pounds

Pallet Positions: 18 pallet positions

Passengers: 58 total (normal operations); up to 114 total (contingency operations)

Aeromedical Evacuation: 58 patients (24 litters / 34 ambulatory) with the AE Patient Support Pallet configuration; 6 integral litters carried as part of normal aircraft configuration equipment

First Air-To-Air Refueling

Unless you consider The No-Hose Method

The Air Mobility Command has a 7 part history of Aerial Refueling posted on the Air Force Web Site - AF.MIL - Information provided here has been compiled mostly from those articles.

Part 1 - Tankers: From A ? To Today's Fight

Part 2 - Air Refueling Development Lags

Part 3 - The 1930's: A Lag, But Not The End Of Aerial Refueling

Part 4 - U.S. Military Aerial Refueling: Extending 'The Reach'

Part 5 - History Of Aerial Refueling: Fueling The Fighters

Part 6 - Development Of THe Modern Air Refueling Aircraft

Part 7 - Vietnam: The First Tanker War

Further Reading:

Department Of Veterans Affairs "America's Wars"

Global Vigilance ~ Global Reach ~ Global Power For America

Snapshot of the Air Force Reserves